The following essay was originally among a series about famous managerial moves…

If he’d never done anything except discover Honus Wagner, Ed Barrow would hold an important place in the National Pastime’s grand history. No, he wouldn’t be in the Hall of Fame today – which of course he is – but still, an important place.

Barrow did so much more than discover Wagner, though. He’s in the Hall of Fame largely because he presided over a Yankees dynasty that won 14 American League pennants and 10 World Series in his 25 seasons as (de facto) general manager.

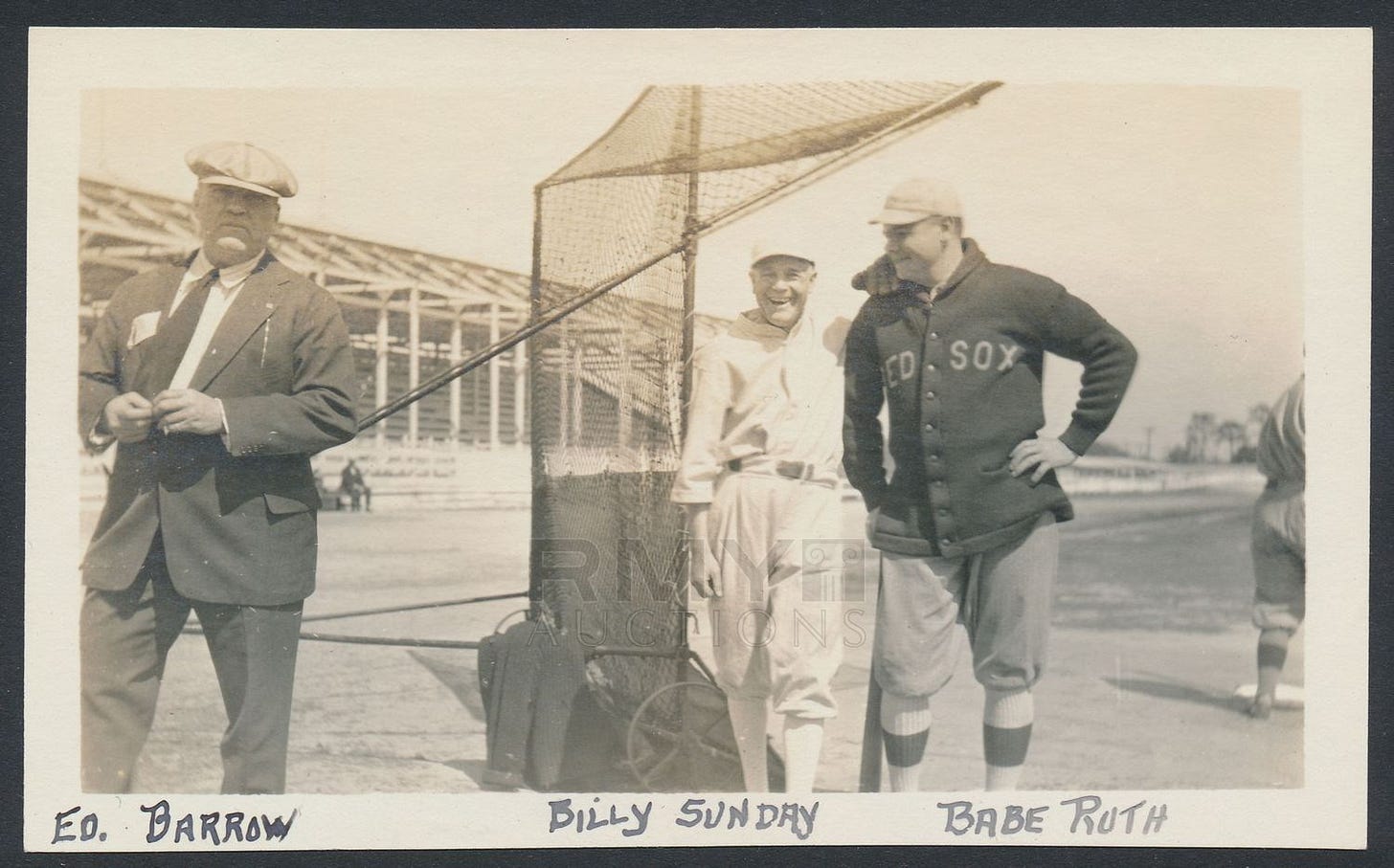

By the time Barrow took over as field manager of the Boston Red Sox in 1918, he’d already worked as manager or co-owner of various professional teams, and also served as president of both the Atlantic League and Eastern League. But the best was yet to come.

In 1918, Barrow guided the Red Sox to a pennant in the war-shortened season, followed by a victory over the Cubs in the World Series. Barrow’s top left-handed pitcher, young George Herman Ruth, won only 13 games during the season, but he won both his Series starts against the Cubs, allowing only two runs in 17 innings.

Before Barrow took over, Ruth had never played any position except pitcher, not even for an inning. What he had done was establish himself as one of the more potent hitters in the league, position be damned. And Barrow would take advantage, starting the Babe in the outfield or at first base in 70 of the Red Sox’s 126 games (in the war-shortened ‘18 season).

Still, Ruth’s brilliance in the World Series as a pitcher made a hefty argument for his continued, and continuing, greatness as a pitcher.

So what would Ruth do? Continue his double duties? Despite his public resistance to such duties?

Before the 1919 season, Red Sox owner Harry Frazee made Barrow’s decision a little easier when he traded/sold Duffy Lewis to the Yankees, thus creating a hole in the outfield. On the other hand, in the same deal, Frazee also dispatched starting pitcher Dutch Leonard; in 1918, Ruth and Leonard had combined to start 35 of the Red Sox’s 126 games.

So it was hardly a gimme for Barrow. According to Ruth biographer Leigh Montville, “An off-season poll of managers in 1918 indicated that most of them thought the Babe should be a pitcher.”

And Barrow would later write in his memoir, “I have always felt that if Ruth stuck to pitching he could have been one of the greatest left-handers of all time. Maybe he would have been the greatest. He had it in him.”

I don’t doubt Barrow’s sincerity, or the sincerity of Barrow’s peers who thought Ruth should keep pitching. But I might take some slight issue with their analysis, or maybe their imaginations. Most of them probably just couldn’t imagine what sort of hitter the Babe would become. Also, most of them were probably unconcerned by Ruth’s strikeout rate on the mound, which declined by more than 50 percent from 1916 to 1918.

Obviously, in retrospect it’s easy for us to say that making Ruth a full-time hitter was the smart thing. But it wasn’t so obvious at the time. Which is why you’re reading this essay.

When the 1919 season opened, Ruth was taking “his regular turn” among Barrow’s starting pitchers, even while playing in the outfield on most of the days he didn’t pitch ... an “experiment” that Barrow said would end if the Babe went into an extended slump. He started five games on the mound in May, five more in June.

His last June start came on the 25th, and he got rocked by the Washington club. In his last 54 innings he’d given up 27 runs, and struck out only 11 batters. Meanwhile, despite a hitting slump that lasted for most of May, his batting line now stood at .303/.421/.599, among the best in the league.

But more and even better was coming.

After that poor start against the Senators, Barrow yanked Ruth from the rotation. He would be the manager’s every-day left fielder. Barrow had, as Dan Daniel later wrote, crossed the Rubicon.

Just a few weeks later, though, pitcher Carl Mays quit the team, and Ruth went back in for a few turns. He pitched poorly in all three of his starts, and was back out of the rotation when rookie (and future Hall of Famer himself) Waite Hoyt joined the club.

Getting off the mound seemed to energize Ruth. On the 14th of August, he set a new American League with his 17th home run. On the 5th of September, his 25th homer broke Buck Freeman’s National League (and major-league) record ... at least until some persnickety figure filbert unearthed Ned Williamson, who’d hit 27 home runs in 1884. On the 24th, Ruth passed Williamson, and three days later he finished his historic, record-setting, awe-inspiring season with his 29th home run.

Before the season, 29 home runs had been practically unimaginable; in fact, nobody else in either league hit more than 12 that season, and nobody else on Ruth’s own team hit more than three.

Granted, if 29 had been unimaginable, what about 54? That’s how many home runs the Babe hit in 1920 ... for the Yankees, having been sold to that club by Red Sox owner Harry Frazee. Barry stuck around as Red Sox manager that season, then moved to the Yankees as general manager in 1921, where he would again enjoy a highly fruitful relationship with the game’s greatest player.

“That Barrow radically altered the national pastime by converting Ruth into an outfielder goes without saying,” Tom Meany, another of Ruth’s many biographers, would later write. “Nor can it be brushed off by assuming that if Barrow hadn’t made the switch some other manager would have, for Ruth already had played under two Boston managers, neither of whom was willing to sacrifice the Babe’s great pitching skill for his daily batting power.”

I think it is true that some manager would eventually have made the switch. If not in 1919, then 1920. If not in 1920, then ’21. Still, Barrow spent decades establishing himself as one of the more astute baseball men who ever lived. And while this might not have been the most astute thing he ever did, it might have been the biggest.

As Barrow himself later wrote, “Many people have said that when I changed Babe Ruth from a left-handed pitcher into a full-time outfielder, I changed the whole course of baseball.”

This was very interesting. Not many that I can recall talk about this, that Ruth might not have had any choice but to switch to outfield full-time as his pitching declined. Doesn’t diminish him in any way, just highlights how hard it is to do both well, which makes what Ohtani did in his fully healthy two-ways seasons even more remarkable