It’s a funny thing, how much players seem to care about the numbers on their backs. For many (or perhaps most) of them, that number, however ignored or forgotten by nearly all the fans, so often comes with intensely personal feelings.

When numbers first appeared on the backs of jerseys in 1929, the players had little choice in the matter; they simply wore the numbers the equipment managers gave them. The world-famous New York Yankees were the first to wear them in all their games, and their single-digit numbers were simply assigned according to a player’s usual spot in the batting order; that’s why Babe Ruth was 3, Lou Gehrig 4.

But that system didn’t last long, as players had all sorts of personal reasons for wanting particular numbers (and of course most players didn’t have usual spots for long, except pitchers and they couldn’t all be 9). One of my favorite traditions: knuckleball pitchers wearing 49. Charlie Hough began wearing 49 in 1970, and Tom Candiotti adopted 49 when he came up in 1983, and Tim Wakefield joined them in 1992, wearing the number throughout his fine career (alas, R. A. Dickey, baseball’s last great knuckleball pitcher, did not join the fraternity).

Over the years, most players have assiduously avoided wearing No. 13, but there have been notable exceptions. Perhaps most famously, ill-fated Ralph Branca wore 13 in 1951, when he gave up history’s most famous—or infamous, if you were a Brooklyn Dodgers fan—home run, the Shot Heard ‘Round the World. Branca switched to 12 the next season ... but then, somewhat heroically, switched back to 13 in 1953 (although that lasted only a few weeks, until he was traded to Detroit).

Honolulu native Sid Fernandez debuted with the Dodgers in 1983, pitched for the Mets from 1984 through 1993, and finished his career with brief stints in Baltimore, Philadelphia, and Houston. But throughout his career, he always wore the same number: 50, commemorating the 50th state in the Union.

Long before Sid Fernandez, a pitcher named Bill Voiselle probably was the first to honor his home territory with the number on his back. In 1944, Voiselle feasted on wartime hitters and won 20 games for the New York Giants; that season he wore the perfectly conventional No. 17. In ’47, still pitching for the Giants, Voiselle switched to 30. That June, though, when the Giants traded him to the Boston Braves, Voiselle requested—and was given—the number 96, which immediately became the talk around baseball.

Why 96? Because Voiselle actually grew up in a little South Carolina town called Ninety Six (for reasons still unknown). And Voiselle wore 96 for the rest of his time in the major leagues, first with the Braves and then (briefly) with the Cubs.

For decades, Voiselle was the only player to wear 96 on his back during the regular season. In 1996, when Mariners pitcher Mac Suzuki debuted in the majors, he too wore 96. But Suzuki pitched in just one game before going back to the minors, and when he returned two years later, he donned No. 41 instead. (In the last few years, perhaps due to the massive increase in MLB bullpen jobs, others have worn 96, however briefly.)

Perhaps the strangest number, though, was worn by longtime major leaguer Benito Santiago. It seems that Santiago preferred No. 9. But Santiago was a catcher, and found it bothersome that the leather strap holding his chest protector together ran right through the middle of the 9.

Santiago’s solution? 09, with the strap running between the digits. He wore this somewhat absurd arrangement with the Padres in 1991 and ’92, and the Marlins in ’93 and ’94. Santiago then switched to No. 18 with his next three teams, before returning to the single-digit 9 in 1999, his only season with the Cubs.

Meanwhile, a number of players have worn 00, most notably stars Don Baylor, Bobby Bonds, Jose Canseco, Jeffrey Leonard, and 1940s hurler Bobo Newsom. Leonard wore it the most, but journeyman pitcher Omar Olivares probably wore it the best. After all, for Olivares 00 wasn’t just a number; it was also his initials.

By the same token, a number of players have worn the single-digit 0 to denote one of their initials, including Oscar Gamble, Oddibe McDowell, and (most recently) Adam Ottavino. But the champion 0 wearer is Al Oliver, who wore the digit for nearly half his long career, including in four All-Star Games.

Perhaps my favorite oddball number is 88, for the simple reason that I’ve got a vivid memory of heckling Rene Gonzales for wearing what I suggested belonged on a football player, not a utility infielder.

Why did Gonzales wear 88 for most of his oddly long career? He once described the number as “consistent and infinite,” and grew tremendously attached to it, claiming the digits with five different teams. He also once claimed, “I made that number. I came up with it. Nobody had ever worn it in the history of the game.”

Which is true, at least in the white major leagues. In 1987, Gonzales took the field on Opening Day wearing 88, and he was the first. Later that season, Dodgers rookie Mike Ramsey also adopted the number—it was his third of the season, after previously donning 37 and 56—but Ramsey didn’t play in the majors after ’87, so Gonzales had the (baseball) field all to himself for a few years. The number has never been otherwise popular, but Rays relief pitcher Phil Maton has kept Gonzales’ consistently infinite tradition alive, and a few others wore 88 in 2023.

Finally, no discussion of double digits would be complete without 99.

That lofty number is not a modern phenomenon in the majors. Not quite.

In the 1940s, Charlie Keller was a fearsome slugger with the Yankees, and wore Nos. 9, 15, and 12. In 1950 and ’51, he wore 27 as a Tiger. And in ’52, he returned to the Yankees for just two games … and for some reason, wore 28 in the first, and 99 in the second.

Keller was the only 99 until 1977, when Willie Crawford wore the number for Oakland in his last major league season. Crawford would be the last for a while.

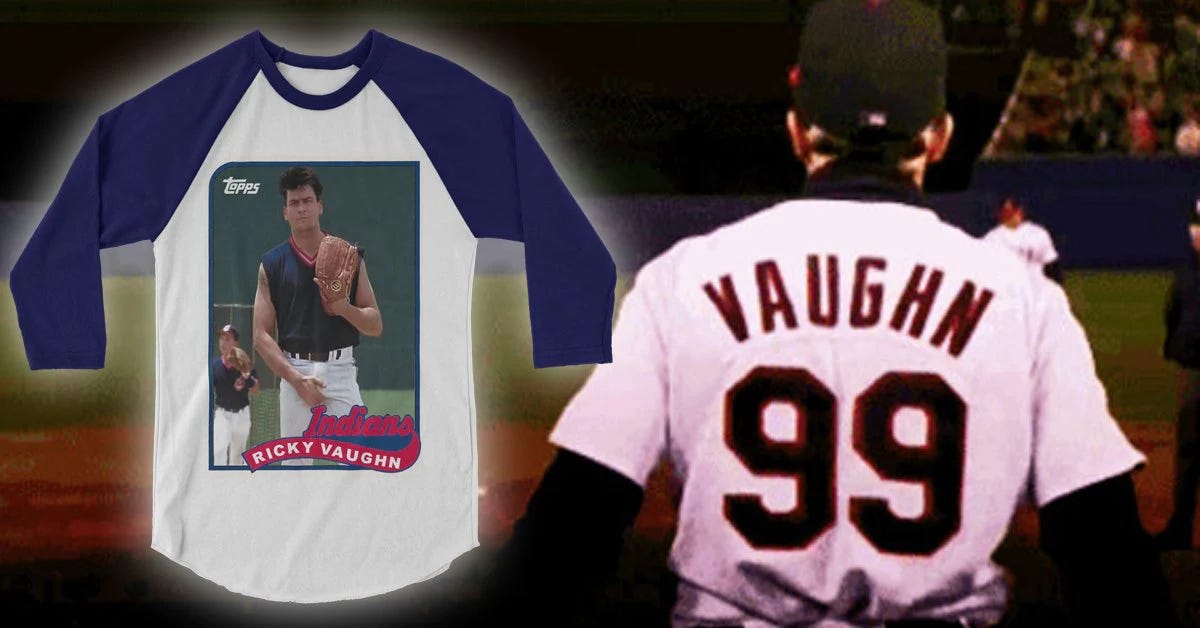

In 1989, though, No. 99 became famous when a flamethrowing reliever named Ricky “Wild Thing” Vaughn starred for the surprisingly good Cleveland Indians, wearing 99 all the while.

In a movie.

And in the best example of baseball life imitating baseball art since Eddie Gaedel pinch-hit for the St. Louis Browns, in 1993 Mitch “Wild Thing” Williams donned No. 99 while pitching for the real-world Philadelphia Phillies. And it was while wearing 99 that Williams gave up Joe Carter’s World Series-clinching home run in Game 7 that same fall.

Sometimes life imitates art, and sometimes you throw fastballs where you shouldn’t.

Another fun one is Joe Medwick's number 77 with the Dodgers in 1940-41, alluding to his NJ record 77 points in a HS basketball game.

Also, something I learned in investigating a Carl Hubbell baseball card "error" is that players were assigned numbers in the 1934 ASG that they pinned over their team-issued jersey numbers. If you look carefully at photos from the game, you will see these number flaps. I've collected some of the photos in this article: https://www.hobbynewsdaily.com/post/the-slick-est-cameo-in-all-star-history

There's a long tradition of Venezuelan players (mostly but not exclusively shortstops) wearing #13 as well, going back to Davey Concepcion: Ozzie Guillen, Omar Vizquel, Edgardo Alfonzo, Asdrubal Cabrera, Salvador Perez, Ronald Acuña Jr...